Yesterday I was honored to participate to a debate in the European Solidarity Center in Gdansk, located in the historical site of the shipyards where the movement Solidarność arose in the early 1980s. The topic was, “what is solidarity”. Here is text of my speech.

*

I am deeply honored to speak about solidarity here, where Solidarity (Solidarność) was born but is also kept alive by the oustanding work and the celebrated Museum of the Center.

To debate of such a challenging topic, let me start with a fable known to all of us, a useful tale for me of how to understand solidarity in the current quest for the European Union to survive.

It is Aesop that wrote it first, rewritten centuries later by French poet Lafontaine, of an ant and a grasshopper. During the summer, the former works hard and saves food for the harsh winter season, the second dances, quite well, but does not save for bad times.

By now you will have already guessed who’s who in the current European situation: Italy (and Greece) and southern EU are the lavish grasshoppers and Germany and northern EU the thrifty ants. A stereotype? Not so much if you look at the summer season of the euro, between 2000 and 2005, when public spending in Italy was definitely higher than in Germany, allowing public debt to rise exactly when it was supposed to go down, in good times.

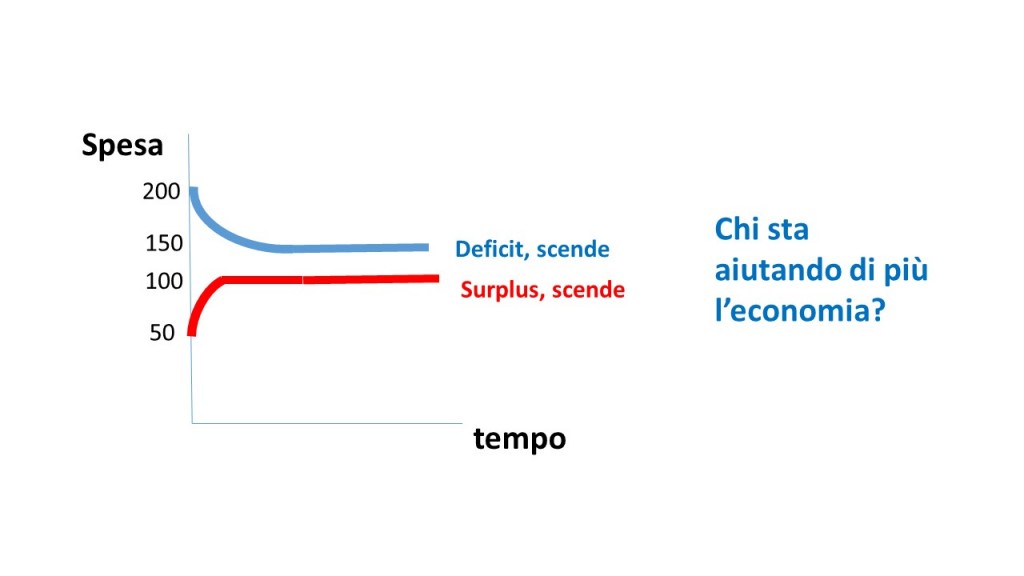

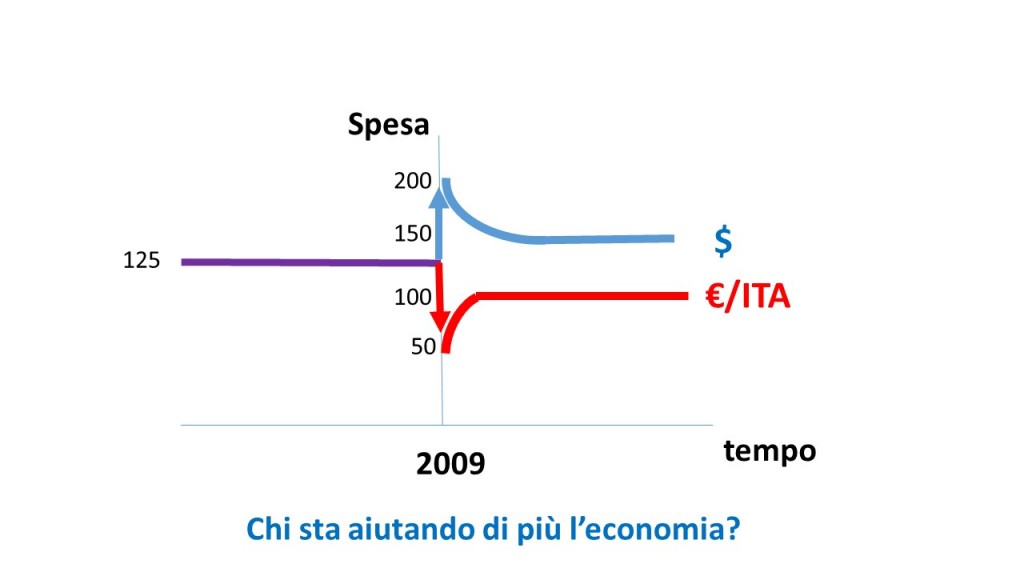

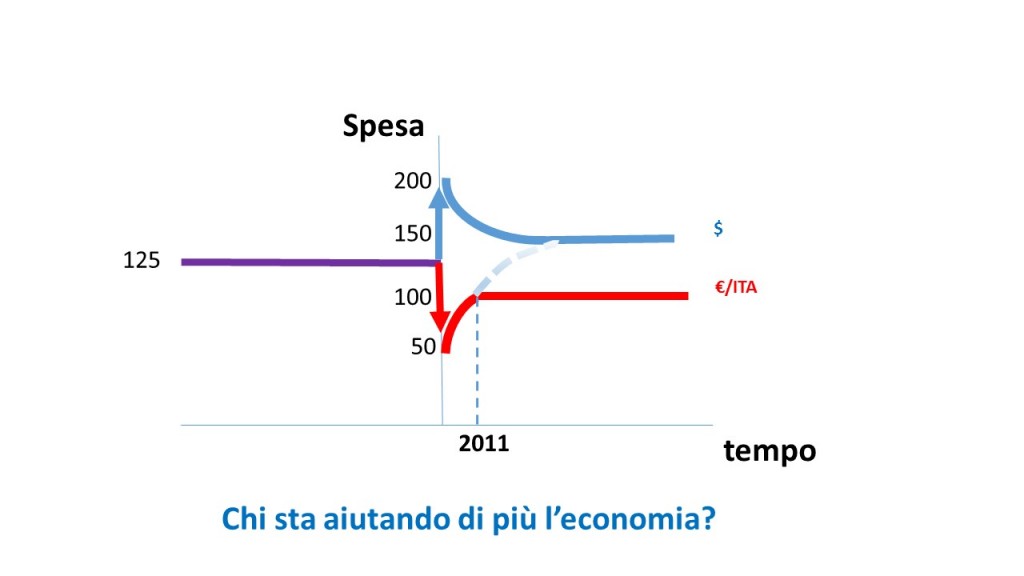

It would however be very easy for me to show you, using Eurostat data, that this stereotype is untrue after the winter started to surround the European Union: between 2010 and 2016 total real public spending in Italy has gone way down (in particular public investment, by 30%!) while it has moderately gone up in Germany. So, during the second economic crisis which started in 2011, Italy would be the austere ant and Germany the timid cricket; but this is a bit beside the point, since perceptions and stereotypes matter a lot, almost more than data when it comes to solidarity issues.

So, to go back to the tale which you know so well, when the winter arrives, the ant survives well in its warm house. The grasshopper freezing to death knocks on the ant’s door and asks for refuge. In Lafontaine’s fable, the ant shows no solidarity at all, and lashes the famous quote in French, “Danse”, tantamount to “die”.

A telling tale indeed, as this is what has been repeatedly said to Greece and Italy in these past years of forced austerity in bad times. Also, not a brilliant solution for Italy, and therefore for Europe, if our aim is one of keeping the Union alive (a wish that an increasing numer of voters in Italy and other Southern countries are questioning, arguing that national sovereignty is the way forward, a belief I should add I do not share but respect, as it deals with an honorable sentiment, the one of which flag most represents each one of us).

I urge you however to cross the Atlantic through You Tube and download the Walt Disney Version of the same fable, it lasts for 10 minutes at most. In the cartoon, the first 9 minutes mimick exactly Aesop’s and Lafontaines’s tale. In the 10th minute however everything changes. The grasshopper knocks on the door, the ant opens, welcomes the almost frozen insect in the warm room, offers a warm soup, and then says to the grasshopper (in English): “Dance”, and happily goes on to enjoy the show of the artist with great gusto and renewed friendship. Solidarity is there, and allows both parties to rejoice more than had they remained alone and not united.

*

It is likely to be the case that this last tale has the right happy ending for any true European. It leaves however some open questions. First and foremost, the one of where does the ant’s solidarity come from. Since we are so much in search of solidarity these days, it might come in handy to find out.

The cartoon itself helps to begin sketching an answer.

It came to my mind, watching it, that solidarity not only can coexist with diversity, but I would go as far as to say that diversity is a necessary pre-condition for solidarity: only in its presence, that is, we may be able (not always) to talk about solidarity. When we all are the same, when we perceive ourselves as one, then solidarity disappears, to become something else, a sentiment of brotherhood (fraternité!), patriotism, like a river flowing naturally into its ocean and becoming salted water.

Also, it seems to be obvious from the cartoon that the ant does not open its house to all the animals in the world, but only to a restricted category, in this case the one of the grasshopper. When dealing with solidarity, the diversity we need is a limited one.

I am ready now to give a definition of solidarity based on these intuitions from the cartoon: it is, I believe, a non-universal moral responsibility we owe to certain categories of people different from us, a responsibility to come to the rescue of “the other” in times of trouble.

By the way, we are today speaking in the Main Auditorium of this beautiful Center and just a few minutes ago I was reminded by its Director that even the Solidarność movement in Poland was not homogeneous: it united, by connecting them, many different social groups suffering, often for very different reasons, from an oppressive Communist regime.

So framed, solidarity requires more explanations. Why do we feel we owe something to “them”, the “others”? Again, a necessary (but not sufficient!) obvious condition is that, typically, we must have a common history, often a very strong history in common. We are not here to debate solidarity of Italians or Poles to Chinese people, nor are Chinese citizens debating their solidarity towards us, and for a cause: our shared history is little. Maybe one day, we will discuss that too, but not today in this century.

*

However, when that diversity is very strong, no matter what history one has in common, solidarity to arise requires a first element, which I deem indispensable: time. Solidarity, like all moral bonds, grows with time, it can’t be created out of the blue one day. This is relevant for the current dabate in Europe, as I don’t think that the recent proposals of Macron, president of France, to switch to a common budget and to a unique Minister of the Economy (located possibly in Brussels) will do the job. It will be simply a Minister of no solidarity just like today, if we have not become first willing and convinced that we must exercise solidarity. How can I be so sure? Well, for one, because the history of a successful union of diverse states (with a common currency), the United States of America, teaches us otherwise.

A Federal budget and a one man only in charge of it in Washington DC, indeed, took a long time to be approved: exactly in the mid 1930s, 140 years after the formal North American Union was born. Before 1930, a Mississippi plant-owner would have never accepted that a land tax was to be decided in Boston or, for that matter, in Washington DC. Spending, taxes, debts and deficits in the XIX century were predominantly local, just like today in the EU. It took more than 140 years for everyone to accept that Washington could decide for all. A Civil war, the invention of the train that allowed to meet diversity across States, World War I and its push for the US to become a global power, and a crisis like the Great Depression helped the build-up of a Federal system, first proof of the birth of a solidarity across Union members.

This historical evidence by the way generates a second intuition: solidarity needs not only time but also luck to materialize. Anything could have “gone wrong” in 140 years, starting with the Civil War outcome, in the mind of a federalist.

*

Can we force our luck? Can we bend destiny and increase the likelihood of generating solidarity before this one has had the time and luck to survive and grow? That is a hard question to answer but inevitable to be asked. Let me try to see two possible ways of doing it, again based on intuitions from our past experience.

First, through a crisis. Crises can be great moments to generate solidarity, if only because the call for help of those who suffer is so strong. By coming to the rescue in times of crisis one extends an invisible loan that will always be repaid because of gratitude, and will generate an essential component of any social contract among diverse people: trust. In the 1930s, Franklin Delano Roosevelt had the leadership and the capacity to leverage the crisis and generate trust across the country, ending up uniting for the first time the United States of America with a social insurance scheme of support for those in trouble. After a few years that technical scheme would change into a true sentiment of solidarity and finally one of patriotism that would surpass the one for one’s own State: the river had found its way into the ocean.

But, what if we were to waste the opportunity that comes with a crisis and let it instead increase inequalities and income differences? Then, data show, trust collapses, i.e. exactly what we have seen happening in Europe since 2011, when the support for the EU project has started to crumble in just a short number of years. Lack of leadership, lack of democratic representation for those who suffered are to be blamed but, what matters most, the window of opportunity was missed and skepticism for the future of the European Union has grown vastly across the Continent.

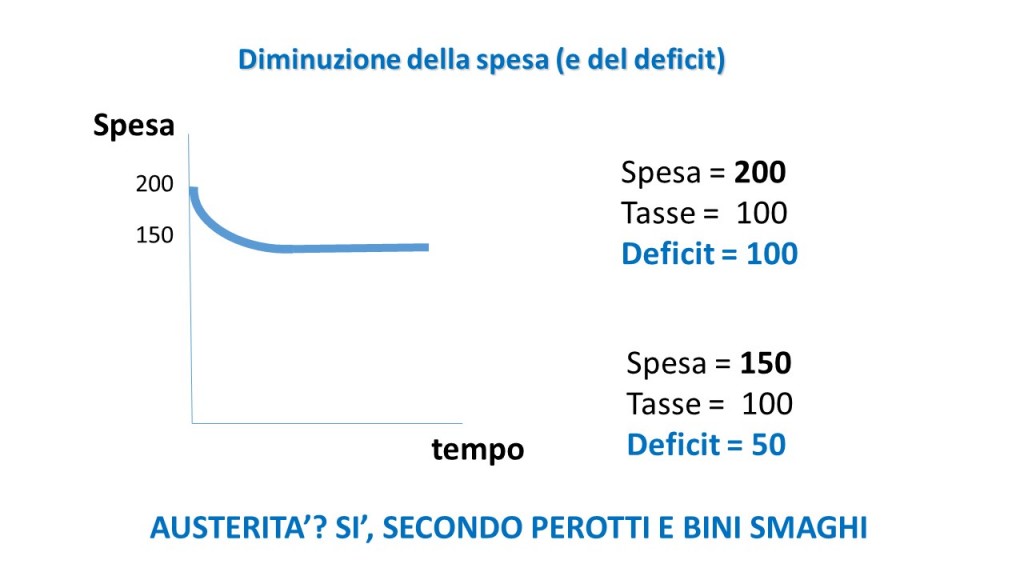

There is however a second instrument in our hands to try to force luck and destiny: the Law. Emmanuel Kant used to say that good morality does not generate good constitutions, but that good constitutions can help building up good morality. Unfortunately here again we Europeans were not wise and did not follow advice from the past or from other countries. We indeed created a new Constitution, started in 2011, the so called Fiscal Compact, but a terrible one indeed. One that does not allow countries, when in pain with low demand for goods and high unemployment, to come to the rescue like it is done all over the world, yesterday and today, with expansive fiscal policies, more public investment that is, that generate growth and more stable public balances. Another window of opportunity to bend luck toward our precious goal of strengthening Europe’s cohesion was missed.

*

Some today claim that a third opportunity will come with the possibility of mutualizing our debts and issuing eurobonds, a de facto direct fiscal transfer from those countries in good shape (Germany) toward those in pain (Italy or Greece). German will not, I am afraid, agree to such a scheme, not now nor in the near future. And, mind you, not for the reasons mentioned typically by Italians, i.e. that “Germans are selfish”. German are not selfish; to the contrary they have engineered, in the last decade of the previous century, the largest transfer of money and resources ever seen since World War II, with an intensity never experiences even in Italy to support its poorer South: a transfer from the West German citizens to the Eastern ones newly returned to the motherland after the long separation of the Cold War.

One may ask: why was such solidarity exercised in this case and is not for Italians or Greeks? After all East Germans may be seen as equally unproductive as the Italians, to follow once againa stereotype. For a simple reason: that East Germans were perceived as cousins of first degree if not brothers, while Italians are only distant fifth or sixth degree cousins. Solidarity to arise today needs more history in common of sharing and understanding.

But this is not necessarily bad news, as it is actually exactly why the European Union project was started. Do not forget that the Union works over time exactly in the opposite direction of a family, where brothers become cousins of first degree, third, fifth…. losing contact. Europe, to the contrary, is supposed to start from cousins of sixth degree and then move … backwards: so that the son of the son of the son of my son will become brother with the son of the son of the son of a son of my German counterpart today.

For that to happen, once again, we need time, and luck. Time that can be gained only in one credible way: by having Germans and Italians today do things that are in their strict national self-interest but that also allow for the common good to arise. Impossible? Not at all.

*

Try to ask German workers if they were to approve of a fiscal reduction in their taxes after so many years of ant-like sacrifices. They certainly would. And part of that bonus would spent … where? Yes, on a Greek Island, dancing, or buying an Italian fridge, reducing at the same the the huge external account surplus of Germany and contributing to development of all other euro countries.

Italy does not need lowering taxes: pessimism is so high that nobody would spend it but rather save it for fears of an uncertain tomorrow. What Italy neeeds now is a huge public investment plan meant to support productivity of Italian firms with better infrastructure, whether material or immaterial, raising demand and GDP and contributing for the first time after many years to reduce its debt over GDP, that has increased with the opposite policies, those of blind austerity.

As much as the German was to learn dancing, the Italian grasshopper would have to show a disposition to do a bit of extra-work, possibly helped by the expert ant: nothing can work better than a convergence of shared values to foster faster birth of solidarity. Italy and Greece in particular would have to provide Germany with ample proof that, since they ask to spend more, they can spend well. Germany could help here too. By agreeing to participate and contribute to the fight against corruption, possibly with the creation of a European Anti Corruption Authority, it would not only contribute to the birth of a critical European public good but would also obtain an extraordinary consensus of 90% of Italians and Greeks, increasing mutual trust and accelerating the growth of solidarity.

It is obvious that such a comprehensive strategic plan would require discarding the non solidaristic recent and unfortunate Constitution of the Fiscal Compact. Taking advantage of the fact that its 5-year performance needs to be judged by year-end then, after the German elections, we would witness the rise of a common NO to its insertion in the European Treaty, releasing the powerful weapon of expansionary fiscal policy coming to the rescue of a stagnating European economy.

By doing so, solidarity would grow faster in the near future and the Union would become stronger, focused on its mission of becoming a global player in defense of human rights, sustainability and culture around the world. A task that only the countries that make up Europe, with their common history, can hope to achieve.