Un fiume amaro, Iva Zanicchi. (C. Dimitri – S. Tuminelli – Mikis Theodorakis)

The Desert, Greece and its Public Sector

”I like the desert. It’s hot there in the desert, but it’s clean.” Lawrence of Arabia, 1962, the movie.

”I like the desert. It’s hot there in the desert, but it’s clean.” Lawrence of Arabia, 1962, the movie.

The Germans. The Greeks. That bloated public sector. Of whom? The Greeks? Think again, by reading the ECB working paper of these 8 researchers.

Yes, the share of public employees over total workers of Germany is only 19% while the Greek one is 29%. But Greece is by no means the worse: Germany’s strongest ally, Belgium, is at 38%, while public-loving France is at 31%.

The German public sector has less university-degree holders than the Greek one (49 against 56%) but, nevertheless, many more in managerial position (26 against 18%). Greek public employees are slightly younger (41 vs. 43 years old) and work basically the same amount of hours during the week (35 vs. 36).

The net hourly wage for public employees is 30% higher in Germany (13 euro against 10), while the mark-up over the net wage in the private sector (a much more relevant measure to gauge the extent to which public sector is putting pressure on private sector wage negotiations and, possibly, on inflation dynamics) is much higher in Greece: 55% against 21%. However, once you take into account not hourly wage but net average (yearly) compensation – 23.000 euro in Germany and 15.000 euro in Greece – the difference in mark-up over average private sector compensations shrinks: 18% in Germany and 27% in Greece (it is 46% in Portugal and 26% in Spain). This is because (in all countries) in the private sector worked hours are higher than in the public sector and so differences decline.

Anyhow, these are numbers that are hard to compare across countries if you do not take into account differences in characteristics that affect wages: age, gender, education, public sector type etc. Once you do that, 3 groups of countries emerge:

Group A, the “private-attentive ones”: Belgium and France, where the premium with respect to private sector pay is almost non existent.

Gruppo B, the intermediate ones: Austria, Italy and Portugal.

Group C, the “public-attentive ones”: Spain, Ireland, Greece and … Germany. The latter, indeed, has a premium of 15% against the 16% one of the Greeks.

So there you go. The Greek public sector is not such a large anomaly one is trying to convince you it is. Yes, the public sector employment is relevant, but not that much more than in many other European countries. It has less managers than the German public sector, even though more of the employees are graduates. There does not seem to be an incredibly negative effect of Greek stipends on private sector stipends that affect directly competitiveness: the public stipend premium over the private sector one is the same as the German one.

The Greek problem, like the one of many euro countries, is one of general productivity and wages, possibly due to an excessive degree of centralization of Greek wage bargaining that disregards productivity. But if you look at the numbers, the growing weight of the public sector in the Greek economy is not so much due to greater waste but to the greater recession and the lower GDP. These two factors have a cause: austerity and a bloated banking sector (whose ROE collapsed from an average 15% in 2005-2007 to a negative number in 2009) whose murky dealings with foreign EU banks led to disaster.

The ECB Working Paper speaks clearly. Actually, data speak clearly, for whoever wants to understand the current dynamics in the EU area and separate truth from lies.

Data, true data, have this fantastic quality. They are like the desert of Lawrence of Arabia: they are clean.

Come salvare la Grecia?

Cancellando tutto il debito pubblico greco dovuto all’estero e assorbendone le perdite nell’area dei 17 paesi euro.

Il debito greco ammonta a circa 300 miliardi di euro, di cui circa 70 dovuto ai greci stessi.

Ripudiare 230 miliardi vuol dire scaricarne il costo, in termini di PIL annuale, sui circa 9200 miliardi prodotti dai 17 paesi: circa il 2,5% del PIL euro una tantum. Per abitante (sono circa 330 milioni, greci inclusi), parliamo di circa 700 euro a persona in un anno. Non poco.

In cambio, cosa otteniamo? Poco sembrerebbe.

Prendiamo intanto atto che la Grecia, che ha già un avanzo primario praticamente nullo o quasi, potrebbe finanziare le sue spese con maggiori entrate, senza ricorrere ad emissioni di bond per molti anni. Anzi, potrebbe essere immaginato un divieto di prestare alla Grecia per i prossimi 10 anni.

Ma ripensiamoci un attimo. Avrete la gratitudine eterna dei greci e la certezza, dato il loro orgoglio, che eventi di questo tipo non accadranno più. Avremo cioè i greci e dunque la Grecia dentro l’euro, perché dentro l’euro si sente cittadino-nazione di pari dignità. Avremo meno sofferenza drammatica in Grecia in cambio di un poco più di (breve) sofferenza da noi.

Avremo creato l’impressione che ogni paese può fare come gli pare tanto alla fine i debiti vengono cancellati e dunque una salita degli spread in Italia, Spagna, Portogallo? Assolutamente no: i mercati capirebbero che quando una casa brucia non c’è tempo per parlare con l’assicuratore, si spegne il fuoco tutti insieme, aiutandosi, per evitare che la casa sia distrutta. Gli spread sono alti oggi perché i mercati non vedono soluzioni, anzi ne vedono di assurde.

Spento il fuoco e salvata la casa, si analizzano le cause dello stesso incidente: ci si accorge che il condomino non aveva adottato le giuste cautele anti-incendio e che gli assicuratori 1) non avevano sorvegliato tanto bene la loro messa in opera e 2) avevano aiutato, con il proprio disinteresse ed a volte con un interesse sconsiderato per guadagni di breve termine, la costruzione di una casa con poche sicurezze e si è fatto molto – da ambo le parti – per nascondere l’informazione di queste carenze nella costruzione da cui si è guadagnato a breve.

Fatta questa analisi si mettono su nuove regole (non di austerità con trucchi contabili da tutti noti ed accettati, ma di riforme vere e sane) con tolleranza zero vera e sincera per comportamenti fraudolenti siano essi greci o europei.

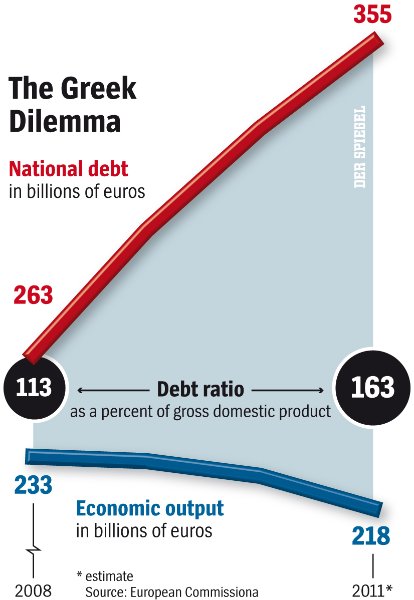

E poi, guardate questo bel grafico fonte Spiegel. Ecco cosa è successo in Grecia alla stabilità con tutte le politiche d’austerità promesse ed attuate (in parte). Il contrario di quello che immaginavamo pensando con modelli economici astrusi dove più austerità uguale più stabilità.

Pensate proprio che con un voto suicida del Parlamento all’austerità alla sua quinta versione, salveremo la Grecia o invece che ci ritroveremo qui tra 3 o 4 mesi a trovare altre risorse (quante già ne abbiamo buttate via?) da prestare perché abbiamo ucciso quella gallina dalle buone uova (direi non d’oro visto il momento che attraversa la Grecia…) che è una economia funzionante e produttiva?

Pensate proprio che con un voto suicida del Parlamento all’austerità alla sua quinta versione, salveremo la Grecia o invece che ci ritroveremo qui tra 3 o 4 mesi a trovare altre risorse (quante già ne abbiamo buttate via?) da prestare perché abbiamo ucciso quella gallina dalle buone uova (direi non d’oro visto il momento che attraversa la Grecia…) che è una economia funzionante e produttiva?

E a quel punto, non sarà inevitabile o pagare ancora di più oppure dire addio alla Grecia nell’euro e con questo aumentare le probabilità che i mercati smettano di credere nel progetto europeo? Il gioco vale davvero la candela? Siamo disposti a correre questo rischio?

The insurer and the Greek house

So the Greek house is on fire.

What do you do if you are an insurer and the house you have insured is on fire? Do you start arguing about the bill or do you rush to save it, to help those who are at risk in the house while also helping to minimize your bill? (thank you A. for this good image).

Obvious answer: you save the house and the people in it. You’ll have time to discuss about who pays the repairs and, especially, how to make sure these things do not happen again. Because, somehow, you have a feeling things did not burn simply by random chance. Somebody has not taken the right precautions. And, guess what? You as an insurer feel a bit guilty. Because you have not checked properly that precautions were taken by a distracted home-owner and, frankly, you know too well that you yourself gained quite a lot in charging less to the home-owner and looking the other way while he was not fixing the house properly to protect it against fire. Isn’t it right Mr. Europe? Mr. Eurostat? Mr. European Commission? Mr. European Central Bank? Where were you exactly when the Greek house was being built on shaky grounds?

I can ask you these questions because, see, I hold shares of this insurance company. And I am a bit tired to see my costs go up and my dividends go down. I hired you guys to do the job as CEOs of this insurance company and it looks to me as if you should be fired. Not only you have not checked how the house was built by looking elsewhere, not only you have still not told me what went wrong (by the way, I am still waiting to know the details of that derivative transaction between Greece and Goldman Sachs), but now you are screaming at the guy whose house is burning to tell him to use “properly” that bucket of water while you look standing by, yelling “Fire, fire!”?

I say enough.

I say you do what I told you to do around last year and you said that it was too crazy to consider. Yes. That’s right. Take all the resources we have and stop once and forever the fire. The way I say it, not the way you said last year which proved WRONG. Not with more austerity which has made the Greek-debt over GDP ratio rise dramatically instead of going down. That was fuel in the fire, not water.

No. You cancel all of the 200 billion and more of the Greek public debt that is owed to non Greek citizens. Now. That will imply paying the bill ourselves, I know. But I prefer to take the loss now once and for ever and concentrate on future business without the looming threat of larger losses in the future. In terms of GDP, since our GDP is approximately 9000 bn. Euro, that would imply a lump-sum loss of 2.5% of GDP this year. Per capita, 700 euro per person.

Yes. Quite a lot. But now see this.

First of all, we allow Greece from now on to self-finance itself through its taxes. Actually, we could even allow for a ban on lending to Greece for 5 to 10 years. Nice prospect for the euro area, not to have to be judged in its cost of funding by a Greek crisis, ain’t it?

Second, we keep Greece in the euro. Can you imagine the impact on Greek citizens? Not only we reduced their large suffering for ever with a little suffering for one year for us, but we also have their full and complete gratitude. Now, isn’t this the safest and most credible loan a country can be owed? Gratitude! You can be sure that Greece will finally implement credibly so many meaningful economic reforms with enthusiasm!

And, third, imagine that, no fear of contagion. Yes, you might argue that markets could say “the cost of defaulting is going down, next is Italy and Spain”. No, it will not work like that. Markets are already pricing, with these huge spreads in the market, the disbelief at the stupidity of austere policies. They can’t wait for growth-oriented fiscal policies plus reforms, driven by Germany first of all.

Once the house will have been saved, it will be time to say “no more”, to the Greeks and everyone else. No more to accounting tricks in public accounts, no more benevolent approval of false accounts because of political reasons, no more lack of transparency regarding what is known but can’t be said because it would (unbelievable to hear, but he actually said it!) roil the markets.*

Stop the fire now, we want the euro and we want Europe, with its values and its geo-political ambitions that can only be fulfilled over the long-run if its values are upheld.

* (M. Trichet’s declaration as to why he will not release details of derivatives transactions of Greece: “The European Central Bank refused to disclose internal documents showing how Greece used derivatives to hide its government debt because of the “acute” risk of roiling (sic) markets, President Jean-Claude Trichet said.”(Bloomberg, November 5, 2010). “The information contained in the two documents would undermine the public confidence as regards the effective conduct of economic policy,” Trichet wrote in an Oct. 21 letter in which he rejected the appeal. Disclosure “bears, in the current very vulnerable market environment, the substantial and acute risk of adding to volatility and instability.”).

Appello Rinascimento: grazie ai tanti studenti siamo vicino a quota 300

Grazie ai tantissimi che hanno aderito, siamo quasi a 300 firme in 3 giorni. L’obiettivo rimane quota 1000: importante che studenti di altre università siano a conoscenza del progetto; se potete comunicateglielo.

Grazie a tutti.

Solo gli spalaneve ci salveranno

Atterro nella neve a Roma alle 23 e mi arrabbio nel NON vedere lungo tutta l’autostrada che porta all’areoporto, lungo tutta la Cristoforo Colombo, lungo tutto il Corso, lungo tutte le strade che mi portano a casa, UNA MACCHINA SPALANEVE. UNA. Mi sarebbe piaciuto vederne una perché credo che ognuno di noi voglia essere fiero di avere uno Stato di qualità di cui apprezza la presenza.

Arrabbiatura più che compensata non solo dalla crescita delle firme (or ora tantissime firme da Archeologia Sapienza arrivate via mail, grazie a Paolo et co.) di studenti all’appello ma dal fatto che Lucio Picci mi segnala come il Governo spagnolo pare si stia muovendo nella stessa direzione verso i disoccupati chiedendogli di lavorare nel pubblico. Gli iberici hanno un sussidio di disoccupazione, che con questa scelta potrebbe trasformarsi quasi in un sussidio all’occupazione, come la nostra proposta.

Chiudo dicendo che in aereo ho letto il bell’articolo del mio collega Pierpaolo Benigno sul Sole 24 Ore sulla crisi.

E’ interessante vedere come è difficile dire certe cose. Ecco la prima frase di Piepaolo:

Le politiche di domanda sono fuori dal gioco dopo che l’Unione Europea ha deciso di legarsi le mani con stringenti vincoli di bilancio e misure di austerità fiscale, mentre la Bce rimane sempre troppo guardinga nei confronti dell’inflazione. Fatta fuori la politica economica keynesiana, rimane comunque spazio per le politiche di offerta. Liberalizzazioni, misure per la crescita, flessibilità nel mercato del lavoro.

Wow. Le politiche della domanda sono fuori dal gioco. Niente spesa pubblica in più, niente minore tassazione. E chi l’ha detto? Solo perché ce lo dice qualcun altro che le politiche della domanda sono fuori gioco dobbiamo noi economisti ritenerle fuori gioco? Il nostro ruolo di economisti pretende che noi si dica quello che serve, non che si prenda atto di quello che qualcun altro pensa.

Tant’è … che se uno continua a leggere l’articolo di Pierpaolo, rimane affascinato dalla lunga, tortuosa ma interessante strada che lo fa tornare nel mondo degli economisti che credono nelle proprie opinioni (sbagliate o giuste che siano) perché non hanno conflitti d’interesse.

Tutta la parte centrale dell’articolo è di fatto dedicata a dimostrare come le riforme (inclusa quella del mercato del lavoro) in questo contesto economico nel breve sono recessive (aggiungo io: e se sono sbagliate, può darsi che lo siano anche nel lungo, ma non apriamo troppe parentesi). Concordo.

Ma è la chiusura che fa da “pendant” perfetto e enigmatico all’attacco del pezzo:

Ma, proprio per la specificità della congiuntura particolare che stiamo vivendo, bisogna liberarsi da modelli e slogan sbagliati. Con il mix corrente di politiche di domanda e offerta, solo una tenuta migliore dell’economia mondiale può farci sperare in una recessione meno profonda. In questo caso sarà vero che ci salverà uno stimolo di domanda keynesiano,… proveniente dall’estero.

Molte domande mi sorgono spontanee leggendoti.

Quindi… torniamo a Canossa? Solo le politiche della domanda ci salveranno? Parrebbe proprio. Ma non erano vietate in Europa? E cosa intendi quando dici “dall’estero”? Dalla Cancelliera Merkel, come chiediamo da mesi? Ma allora, Pierpaolo, diciamolo esplicitamente! Chiediamo a Monti di chiedere alla Merkel l’espansione fiscale tedesca che si meritano i cittadini europei!

E poi, aggiungo io come tocco finale, con l’espansione fiscale in deficit della Merkel, ricordati che può esserci l’espansione in pareggio di bilancio di noi paesi cicala che tu temi: ma non dovresti, perché se la facessimo, questa maggiore spesa pubblica, tutti questi spalaneve, finanziati da tasse, vedresti il PIL ripartire e il rapporto debito-PIL scendere, assieme agli spread. Lo dice la Banca d’Italia, mica io….

Good Morning Poverty.

So, a version of the letter to the IMF by Greek leaders was put out on the web last night.

Dunque. Una versione del testo del documento inviato dal Governo greco al Fondo Monetario Internazionale ed alla Troika è stato pubblicato la scorsa notte.

It documents what Greece will/should/intends(?) to do in the next future to obtain further financing from official institutions. The FT today correctly argues that this deal “stands only a small chance of placing the country on the path to high growth, higher employment and financial stability”.

E’ il documento con la manovra prevista per ottenere lo stanziamento dei fondi, la morfina per lenire il dolore ma non per curare.

If you flip along the pages you will see that it is a scan of a version that has been read, underlined, commented in Greek. Flip them till you will see this.

Se sfogliate le pagine del testo scannerizzato vedrete commenti (in greco), sottolineature, e poi questo.

It attracted my attention because of the sketches. What did they mean? Who did them? A bored journalist? A pensive Greek Minister during the meeting were measures were described? Is it a fake?

It attracted my attention because of the sketches. What did they mean? Who did them? A bored journalist? A pensive Greek Minister during the meeting were measures were described? Is it a fake?

Ho guardato subito ai disegni. Chi li ha fatti? Un giornalista con tempo da perdere? Un Ministro greco nel meeting dove sentiva sciorinare i numeri? E’ un falso?

Then my eye loomed, over the sketches, over that cancelled sentence. What did it say? Why erase it? I asked my friend Aris who is here in Denmark with me. “Good morning poverty“, he smiled. It is a Greek say, not necessarily with an angry slant. History, with its repeated dynamics of power, has nothing to teach to a Greek.

E poi il mio sguardo è caduto su quella frase cancellata, in greco. Per fortuna ho accanto a me il mio collega greco che mi ha spiegato con un sorriso: “significa buongiorno povertà”. Buongiorno povertà. Pare che non sia, mi dice Aris, necessariamente una espressione astiosa. Un prendere atto. Della Storia, che si ripete.

The sea and the fire

Beautiful Denmark. Copenhagen, with its bikes and the students that slide over them as if skating. I like Copenhagen, its elegance, its harshness. Its brick-houses that speak of gusts of winds over the sea that smash against them, protecting fishermen once they are back home. The sea and the safety net, I think.

Beautiful Denmark. Copenhagen, with its bikes and the students that slide over them as if skating. I like Copenhagen, its elegance, its harshness. Its brick-houses that speak of gusts of winds over the sea that smash against them, protecting fishermen once they are back home. The sea and the safety net, I think.

Yesterday with Danish pension fund managers discussing about Italy and Europe. So important to bridge differences. I was asked as to whether Italy would ever accept decline in nominal wages of 20% (like the ones that are added onto Greece now) and I said: never. But the most important part is that I was surprised, in Italy simply nobody is even considering this as a possibility. But we would accept decline in real wages driven by inflation, if inflation were in our hands as it is in Denmark with its Danish Central bank. What we have now in Italy is decline in real wages due to a recession: the size of the pie is getting smaller and smaller. We can’t protest against it, because there is no decree, only less capacity to produce wealth and happiness, as they instead do in Denmark (see video).

We discussed about raising further taxes in Italy, and I try to convince them that no, either we do it as the Danes do it, more taxes only for more spending, so that we multiply income, or no thank you. We have done it so many times, more taxes, less income, more budget deficit, more debt, that we should know better, shouldn’t we?

I tell them that in Italy right now we are very much talking about importing the Danish labor reform, with unemployment subsidies and I say to them: “pray we don’t, the morning after you will have Italy with 25% unemployment, all lining up for a subsidy”. They smile, and they know I am right. There is not one ideal policy for all countries of the EU. Europe is diverse, and together our diversities are a strength. Separated, our diversities become a handicap, a way of fighting and bickering.

I meet with my Greek colleague at the Conference and they, the Greeks that teach in universities, the intelligentsia, are ready to unite with other professors in other Southern countries against the countries that require austerity from us. It makes me sad, this division of North and South of Europe. We are so potentially capable of working together, but distrust is mounting because of the wrong policies. It is crazy, I agree, this package of austerity that has just been approved for Greece, instead of accepting to share the burden for Greek citizens and support a 100% default. “How will you be able to cut wages further?” I ask him. “With rents not going down? How will people pay for the house?” he replies. “Maybe deflation will bring rents down”. “Before that, houses will be burned”.

Our House is burning. And no firefighter is in sight.

150 euro o 150 milioni di euro? Gli sprechi dei Ministeri

Abbiamo dunque una seria e condivisibile lettera a tutti gli impiegati della Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri e del Ministero dell’Economia di rispettare il vigente codice etico e di non spendere in convegni.

Bene, anche se per esperienza personale vi dico che è da anni impossibile o quasi avere anche meri patronati per convegni dal Ministero dell’Economia, altro che soldi. E che restringere i convegni, che il Ministero ha fatto spesso di grande qualità, significa rinunciare, per piccole spese di rimborso spese del relatore, a personaggi che possono insegnare tanto su come far funzionare meglio l’economia italiana. Siamo alle solite: sappiamo quanto costa la Pubblica Amministrazione e non cerchiamo che raramente di misurare il valore aggiunto di quel costo (che può esser negativo ma anche, spesso, positivo).

Mi sconvolge un poco invece apprendere dall’esistente Codice Etico, che si possono accettare doni fino a 150 euro: mi pare una cifra enorme e forse farebbe il Governo a ridurla drasticamente. Tra l’altro, mi fa notare qui una collega italiana al convegno di Copenhagen, e se uno facesse 3 regali da 149 euro a distanza di qualche settimana?

Vediamo cosa fanno negli Stati Uniti, così per esempio (maggiore informazione su altri paesi qui):

“Un impiegato può accettare doni, non sollecitandoli, che abbiano un valore di mercato aggregato di 20 dollari o meno per occasione, purché il valore aggregato di mercato dei singoli doni per una persona non superi i 50 dollari per anno solare”. Seguono abbondanti esempi, quali: se ricevi due regali, uno da 18 ed uno da 15 dollari, deve rinunciare ad uno.

Che aspettiamo ad adeguarci? Mi pare che 150 euro siano troppi.

E poi basta di concentrarsi su 150 euro, puntiamo su 150 milioni. Ministro Monti, lei ha idea se presso il “suo” Ministero dell’Economia – che emana annualmente i regolamenti su quali beni sono obbligatoriamente da acquistare presso la Consip SpA – gli acquisti di PC, fax, stampanti ecc. sono tutti fatti presso Consip? Perché non mettere subito on-line tutti i dati sugli acquisti del Ministero con il paragone con il prezzo Consip ed il tipo di bene, così che con un solo clic possiamo verificare?

Non che quello che emergerebbe avrebbe nulla a che vedere con il suo operato, lei è appena arrivato, ma fornirebbe una garanzia ai cittadini che quando lei ordina qualcosa la sua stessa amministrazione di diretta pertinenza si adegua immediatamente a quanto da lei richiesto. E, le assicuro, altro che 150 euro: ho l’impressione che 150 milioni di euro di risparmi apparirebbero magicamente. E così per ogni Ministero. Una volta che li ha sommati tutti, li mette da parte, e li spende, per esempio per fare nuove carceri o manutenzione di carceri che cadono a pezzi, così rilanciando PIL ed occupazione e riducendo il rapporto debito-PIL.

Basta un clic.

Leader per sempre

Sono in viaggio, scriverò a intermittenza. A Copenhagen, bella quasi come Stoccolma. In aereo ho letto il bell’articolo sull’importanza dei Presidi nelle scuole americane. I presidi come leader di cambiamento. La leadership è un’arma in più per avere un impatto sulla vita dei giovani?

Sono in viaggio, scriverò a intermittenza. A Copenhagen, bella quasi come Stoccolma. In aereo ho letto il bell’articolo sull’importanza dei Presidi nelle scuole americane. I presidi come leader di cambiamento. La leadership è un’arma in più per avere un impatto sulla vita dei giovani?

Michele Placido nello stupendo Mery per sempre

Dividendo le scuole a seconda della presenza di studenti più poveri, gli autori dimostrano come al crescere della povertà degli studenti della scuola la variabilità nella qualità dei Presidi (misurata dalla qualità dei voti degli studenti al netto di tutti gli altri fattori che possono influenzarla) aumenta. Due possibili spiegazioni: o le scuole dove ci sono studenti più poveri “attraggono” presidi meno bravi oppure i presidi meno bravi si distribuiscono in tutte le scuole ma fanno danni più rilevanti nelle scuole dove ci sono studenti più poveri (o, detta in altro modo, i presidi più bravi hanno in quelle scuole impatti più rilevanti via leadership, l’”arma” in più).

L’altro risultato che mi pare importante sottolineare è che un aumento della qualità del Preside si traduce sì in un miglioramento della crescita dei voti medi degli studenti ma minore di un aumento della qualità del singolo insegnante. Ma, ecco la cosa affascinante, gli insegnanti impattano “solo” gli studenti della loro classe, mentre l’impatto dei Presidi è su tutti gli studenti della scuola, con benefici complessivi ben più ampi del singolo insegnante.

Ultimi punti: 1) specie nelle scuole più povere i Presidi più bravi paiono influenzare la qualità della scuola rimuovendo i professori meno bravi e trattenendo quelli più bravi e 2) nell’analizzare la transizione di scuola in scuola si vede anche che i Presidi meno bravi passano di scuola in scuola senza essere “rimossi” dal loro incarico.

Si ritrovano i nostri Presidi e insegnanti in questa analisi per gli Stati Uniti?

E quanto e come possiamo incoraggiare l’arrivo di bravi Presidi in contesti difficili?