But the key question is what Mr. Draghi proposes to do if countries fail to meet their bailout commitments, as Greece has done consistently and Italy did last year when it backed off promised reforms after the ECB started buying its bonds. The ECB’s only real sanction would be to stop buying or even threaten to sell its bonds—but that would put it back to square one by reintroducing breakup risk. The basic parameters of the new operation are already clear: The ECB will buy bonds of up to three-year’s maturity of any country that applies for assistance from the euro zone’s bailout funds and is complying with conditions demanded in return. The ECB is unlikely to publish yield targets since this could compromise its independence, forcing it to justify what are effectively political judgments. And bond purchases will likely be “sterilized” with the new liquidity mopped up via bill sales to avoid accusations the ECB is stoking inflation. That may lead some to assume the outcome for the euro-zone crisis remains binary: Either the crisis countries, in defiance of all recent experience, accept Germany’s vision of a “stability union” and voluntarily proceed with the prescribed austerity medicine, or the euro zone breaks up. In fact, the Bundesbank’s vocal resistance to Mr. Draghi’s proposed bond-buying hints at a third and more likely outcome: that whatever the ECB announces Thursday will prove the thin end of the wedge. Over time, conditionality will likely be eased, rate-targeting become more explicit and sterilization less strictly enforced. The central bank would become a mechanism effectively for transferring wealth between northern and southern Europe. The result would be the Bundesbank’s nightmare: a euro zone modeled more on Italy than on Germany.

Taken from Wall Street Journal (thank you Bob), a day ahead of the ECB meeting.

Actually, it is not exactly like the WSJ claims. But the idea is there to model with game theory 101 this simultaneous game between the ECB and the Italian (or Spanish) government.

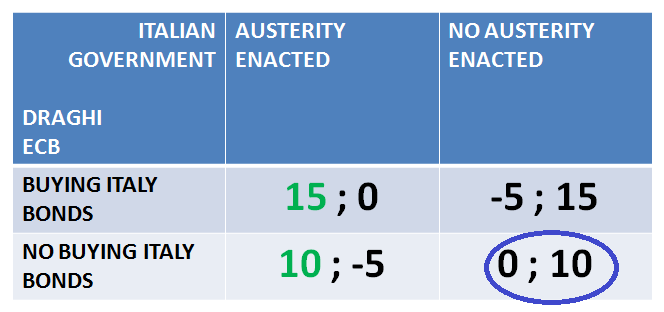

Take a look at this bi-matrix: in the rows it shows actions by a Draghi-led ECB and in the columns the actions of the Italian (Spanish) government. In each cell you read both pay-offs for both actors, separated by a semicolon: first number relates to the ECB, the second number to the Italian government.

For the monent forget about the GREEN-ink that highlights 2 of the numbers and the blue circle, we’ll go back to that later. It looks complicated but it is not: it simply says that Draghi would prefer the most (15) to obtain austerity and buy Italian bonds. If Draghi does not buy the bonds but obtains austerity (without the help of conditionalities) that is a second best (10) since it meets anyway the desire of ECB’s strongest actor, the Bundesbank. But, shifting to the second column, when Italy refuses to do austerity, Draghi gets worried and irritated: -5 and 0. -5 stands for a situation where the ECB buys the Italian bonds and obtains nothing in exchange, not even a bit of austerity.

Looking at the numbers on the right of the semicolon one gets a sense of the pay-offs for the Italian politicians: the best is obviously what is worse for the ECB, namely no austerity and a bond purchasing program from the central bank.

How would this game end? Nash solution points at one equilibrium alone: the blue circle, where no austerity takes place on the side of the Italian government and no purchase of bonds by the ECB.

So under Draghi, no fear for the German Bundesbank: no euro-zone modeled like Italy. But maybe worse: the outcome seems to be a continuation of current affairs, with greater likelihood of a euro break-up.

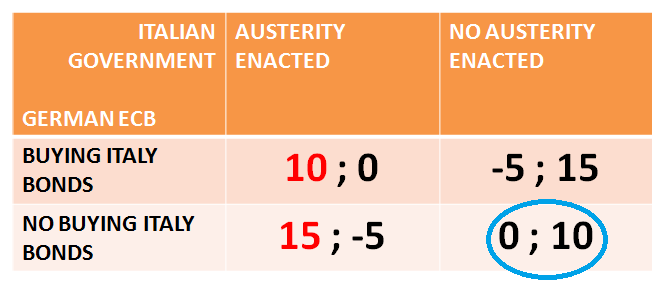

What would happen were the ECB to be dominated instead by the Bundesbank with a Draghi as a mere puppet cornered by a majority of northern euro central bankers?

We model it below (this time check the red numbers and compare them with the green ones above):

The only thing we have changed is indeed the colored numbers, now in red, by making it the best outcome for the ECB not to buy the bonds and obtain austerity, like the Bundesbank indeed desires.

But guess what? The outcome would be the same whether the ECB is Draghi-dependent or not: no austerity, no bond purchases, same risks for the euro. Much ado about nothing?

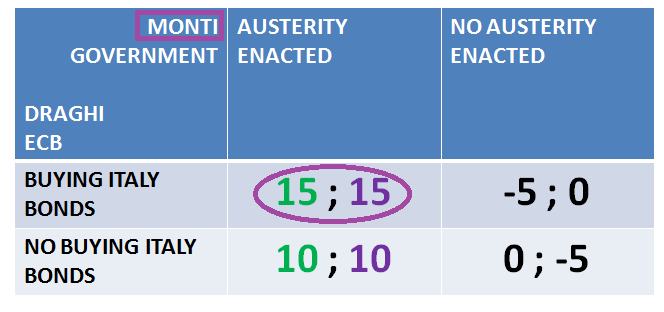

Well, haven’t we forgotten something? Maybe we were not right to model Italian politicians as we did, not austerity-lovers. After all, the Italian government is led by an austerity lover, Mr. Monti. What would happen if Draghi and Monti were to call the shots? Simply, compared to the first bi-matrix, let us change the pay-offs for Italy (look at the purple numbers):

As you can see Mr. Monti, enjoying austerity, creates no dilemma and ensures that the ECB obtains its spread outcome (so does Mr. Monti too).

So the Bundesbank should really concentrate on lobbying Mr. Monti rather than Mr. Draghi.

But, one last time, are we sure that this is the whole story? After all Mr. Monti’s and ECB’s austerity might turn out to be disastrous and lead to greater instability and eventually to the demise of the euro because of the pain that recessions impose on a growing share of the population. After all those numbers above are the pay-offs for individuals and institutions, not for countries. And we do care about countries’ welfare.

Mr. Draghi today said that everything (the crisis) started with the “wrong policies” (of bad (Italian) governments we presume). He did not specify which these bad policies were but one might presume he meant expansionary fiscal policies in good times during the early part of the century. Well, in bad times, austerity is an equally stupid policy goal to implement as it creates suffering and increases the likelihood of a euro break-up.

So while the Bundesbank, Draghi and Monti do share a vision and a goal after all, the key and simple question is: who represents these days in Europe – in the battle for the final choice of the economic policy to adopt – the people of Europe?

07/09/2012 @ 05:10

No. The simple question that arises from your last consideration is: if the people’s interest as you say is not eventually being represented, those politicians and institutions in charge are necessarily representing someone else’s interests that are not those of the people. Who is this “someone else”?

Of course is not a single person nor a mysterious secret society but since you talk about common goals and vision shared by Monti, Draghi and the Bundesbank I have to assume that behind those goals (that you say are contrary and against the interest of the people because they promote austerity instead of expansion) there must be someone pursuing them.

You cannot fight a final battle (your words) if you don’t dare to name your enemy, if the very thought of some kind of transnational interest groups whose “common goals and vision” diverge from those of the people is immediately equated with nebulous conspiracy theories.

Not being outspoken today will oblige us to be heroic tomorrow.

07/09/2012 @ 07:33

“Mr. Draghi today said that everything (the crisis) started with the “wrong policies” (of bad (Italian) governments we presume). He did not specify which these bad policies were but one might presume he meant expansionary fiscal policies in good times during the early part of the century.”

I think the problem is older, with the explosion of the public debt in the 80′s, due to…tax evasion? divorce between bank of italy and treasury?

07/09/2012 @ 07:43

Wow. Then the mistakes would involve many more people totally silent over 30 years.

07/09/2012 @ 08:50

public debt again *^^? please stop kidding…