Debt/GDP ratio at 120%. If your name is Italy, at least so we are told, this number is a monster that needs to be soon vanquished through austerity. If your name is Greece this 120% is the oasis at the end of the (2020) tunnel.

The reality was simple, there was only one debt to be reduced, to zero, the Greek one. Through a default that would have allowed the Greeks to truly gain momentum and gratitude to continue in the reforms they had implemented already in the past decade (see Mc Kinsey’s report on productivity growth in Greece vastly outpacing the European one) and whose slowdown was due to the 2008 crisis, accounting tricks fully known and allowed by EU supervisors and a myopic focus on an irrelevant 3% deficit to GDP displine for an incredible amount of 10 years.

We should have allowed Greek default and shared the Greek burden as citizens (banks are by now free of Greek risk) of the same Continent, as stakeholders of the same ambitious and generous political project. By doing so, we would have reduced the perception of the risk of Greece exiting the euro area through devaluation. Spreads over Bund for Italy would have gone down, and not remained where they are, dumb witnesses of the irrelevance of political action and vision of our current leaders.

Greece looks everyday more like Argentina, ready to default and devalue at the same time, reaping the benefits of large and immediate growth gains through export. It is unfortunate, because there was a huge difference between Argentina and Greece. The former was member of an artificial monetary union with the United States dollar. The latter was and maybe still is part of a fantastic political and cultural project of peace, growth and expansion which is put at risk by a stupid vision neglecting Economics 101 taught in first year undergraduate classes.

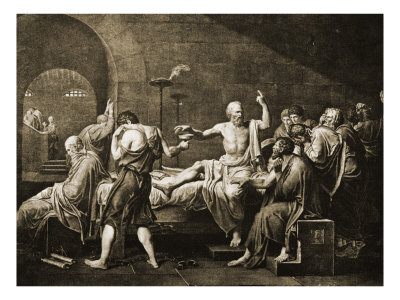

Bob reminds me that in Plato’s account of the trial of Socrates, where Socrates was accused of “corrupting the youth of Athens” and was given the choice to either denounce his philosophies or die by drinking the poison hemlock, Socrates chose death (see figure) and his last words were reportedly spoken to Crito: ”We owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don’t forget to pay the debt.” Asclepius was the Greek god for curing illness. Therefore these words are interpreted to mean that death is a cure and a means to freedom.

Things have changed, oh so much. Once it was that death generated a debt. Today a debt generates death.

23/02/2012 @ 12:59

Caro Prof.,in merito al suo post le sottopongo questo articolo apparso l’altro ieri su La Repubblica. Mi farebbe piacere sapere il suo punto di vista a riguardo. Grazie e buon lavoro

23/02/2012 @ 12:59

http://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2012/02/21/se-la-risposta-alla-crisi-fosse.html

23/02/2012 @ 13:29

E’ con grande onore, con citazioni ricche, dotte e pertinenti nonchè immagini “d’epoca” che dimostri di ben partecipare al nuovo Dipartimento di Studi dell’Impresa, Governo e Filosofia.

L’unica notazione è che Socrate non scelse di morire. Scegliere di morire implica che si possa anche non morire. E questo non appartiene all’uomo.

Scelse, unicamente ma coraggiosamente, quando morire.

Che la stessa precisazione valga per i discendenti d Socrate? Non se, ma quando…

23/02/2012 @ 22:41

i stand corrected.