A few months ago my mentor at Columbia and Nobel Prize Edmund Phelps came to visit Rome for a Tor Vergata Conference. He warned against focusing too much on the current crisis, the one that started and did not end in 2008.

He called it “smoke in our eyes”, distracting us from a much larger and more persistent problem, the one of the “long slump”, the 40 years decline that has occurred in the average growth rate of Western civilization that has left the role of “locomotive of the world” to Asia and other emerging countries since the mid 1970s.

I might argue (and this blog argues) that there is more to this crisis than simply smoke in our eyes and that we should endlessly fight this recession. But Phelps is right: we should also focus into understanding the cause of our (Western long-term) decline.

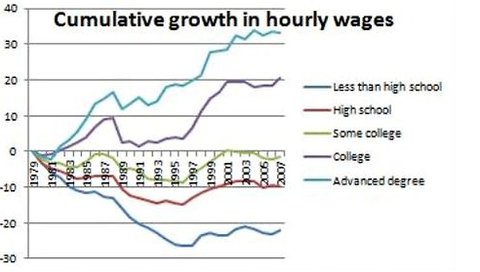

Not an easy job. But I was reminded of all this when I saw this graph in a NYT piece by Laura Tyson, who served as chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Clinton.

It speaks by itself. Scary. I was reading Rajan in Foreign Affairs and while on many things in his piece I strongly disagree with him, I cannot deny he is right when he interprets indirectly this graph by saying:

Think of it this way: when factories used mechanical lathes, university-educated Joe and high-school-educated Moe were no different and earned similar paychecks. But when factories upgraded to computerized lathes, not only was Joe more useful; Moe was no longer needed.

Not all low-skilled jobs have disappeared. Nonroutine, low-paying service jobs that are hard to automate or outsource, such as taxi driving, hairdressing, or gardening, remain plentiful. So the U.S. work force has bifurcated into low-paying professions that require few skills and high-paying ones that call for creativity and credentials. Comfortable, routine jobs that require moderate skills and offer good benefits have disappeared, and the laid-off workers have had to either upgrade their skills or take lower-paying service jobs.

Unfortunately, for various reasons—inadequate early schooling, dysfunctional families and communities, the high cost of university education—far too many Americans have not gotten the education or skills they need.

Others have spent too much time in shrinking industries, such as auto manufacturing, instead of acquiring skills in growing sectors, such as medical technology. As the economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz have put it, in “the race between technology and education” in the United States in the last few decades, education has fallen behind. As Americans’ skills have lagged, the gap between the wages of the well educated and the wages of the moderately educated has grown even further. Since the early 1980s, the difference between the incomes of the top ten percent of earners (who typically hold university degrees) and those of the middle (most of whom have only a high school diploma) has grown steadily. By contrast, the difference between median incomes and incomes of the bottom ten percent has barely budged. The top is running away from the middle, and the middle is merging with the bottom.

The statistics are alarming. In the United States, 35 percent of those aged 25 to 54 with no high school diploma have no job, and high school dropouts are three times as likely to be unemployed as university graduates. What is more, Americans between the ages of 25 and 34 are less likely to have a degree than those between 45 and 54, even though degrees have become more valuable in the labor market. Most troubling, however, is that in recent years, the children of rich parents have been far more likely to get college degrees than were similar children in the past, whereas college completion rates for children in poor households have stayed consistently low. The income divide created by the educational divide is becoming entrenched.

We are discussing of a huge amount of resources – to use a Stiglitz’s expression – wasted, not only in the sense that many are not employed but in the sense that their capacity is, possibly, not put to full use. Low wages (for individuals with low human capital) are a sign of low productivity, yes in that sense, but also that low wages and more inequality depress these people and discourage them from putting to use their full potential. Yes I know, some people say that inequality encourages people to seek higher rewards, but the graph above to me tells a different story.

The more so the more globalization asks from the West to become the brain of the world.

Since what happens in United States is often destined to happen in Europe after a few years, Europeans should work hard to avoid this trend from happening in Europe. Knowing that this cannot be solved with one decree but with a long-term strategy, that looks at the role of teaching, learning, training and re-training. Many organizations in the US are starting to discuss this (see also the Tyson piece). We Europeans should too.